COVID-19: Misinformation and its implications

Viewpoint > This article contains viewpoints of the author and is not intended as a research document

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, there has been great concern about the effects of misinformation online. Much of the debate around misinformation, its potential harms, and what to do about it, has centred significantly around specific events where the tangible effects of misinformation could be measured-for instance, around elections past and future, or the UK Referendum.

The COVID-19 crisis presents a new event around which misinformation can have other significant effects, both tangible and intangible. It can influence people’s behaviours at a time when cooperation and successful compliance with public health and govenrmental restrictions can mean the difference between success and failure in an urgent public health intervention to slow or stop an epidemic.

Viewpoint > This article contains viewpoints of the author and is not intended as a research document

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, there has been great concern about the effects of misinformation online. Much of the debate around misinformation, its potential harms, and what to do about it, has centred significantly around specific events where the tangible effects of misinformation could be measured-for instance, around elections past and future, or the UK Referendum.

The COVID-19 crisis presents a new event around which misinformation can have other significant effects, both tangible and intangible. It can influence people’s behaviours at a time when cooperation and successful compliance with public health and govenrmental restrictions can mean the difference between success and failure in an urgent public health intervention to slow or stop an epidemic.

One simple example we have seen thus far is how rumours about imminent total lockdowns or supply chain failures could easily induce large-scale panic buying, by creating anxiety about the supply of important goods. Being social creatures, people also have a tendency do as others do; thus, seeing (accurate) information about others panic buying itself was enough to inspire others to join in on the fray creating a supply-chain-debilitating positive-feedback loop. Another example, perhaps more dangerous, is the ways that people have downplayed the threat posed by the pandemic or the consequences of not complying, or attributing public health actions to conspiracy theory. We focus on one example of this here.

One of the greatest challenges in trying to combat misinformation is that it can come in various forms. The simplest is blatant, “surface” misinformation, such as news that the Royal Army had been sent fully armed into central London to enforce an immediate lockdown. Sometimes, such information can be very plausible and hard to verify; in such situations, even blatant misinformation can carry. But, in this case, the London rumours were relatively quickly and easily dismissed, as London residents chimed in to verify that the claims were false.

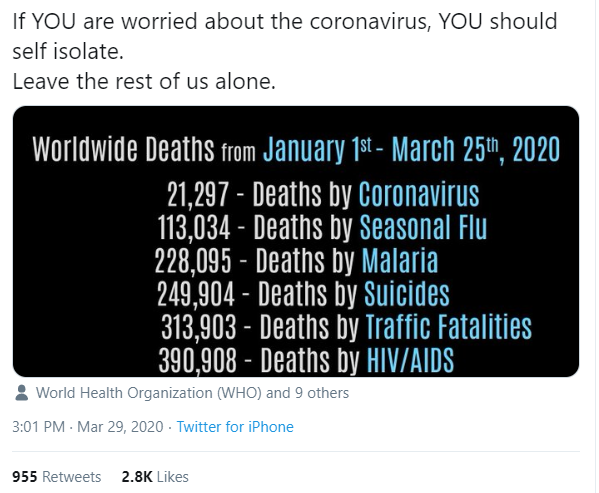

A slightly more insidious form of misinformation is the type that, at its surface, contains correct and verifiable components, but combines them in a way that leads them to a wrong (and potentially dangerous) conclusion. I give an example of a popular tweet from a high-profile executive with over 596,000 followers:

This tweet juxtaposes the number of people who have died of coronavirus to date with an estimate of the number of people who have died from the flu, malaria, suicides, traffic fatalities, and the HIV/AIDS epidemic, respectively over the same duration of time. The implication of the tweet is that since the number of fatalities of the COVID-19 Coronavirus is low compared to these other threats that we now as as society take for granted, society must be overreacting.

If one bothers to cross-check the figures, most of them (distressingly enough) seem relatively on par with those published by the World Health Organisation. So is the author of the tweet right-is the world over-reacting? Any epidemiologist reading this tweet would be able to identify the logical fallacy in the tweet immediately. To the rest of us, this might take a bit of unpacking.

Two immediate ways this is a fallacy is that the numbers representing COVID-19 are at a still early stage in the epidemic, a phase in which figures are still rising exponentially (in fact, in the mere 24hrs between the time this tweet was made at this post had been written, the number of deaths has risen to 33,524-an increase of 60%).

Second, these numbers represent the deaths due to COVID-19 despite an unprecedented global series of interventions put in place by various nations to mandate social distancing and individual lockdown. Without such interventions, the exponential rise in deaths would be even faster, with the World Health Organisation and epidemiologists at Imperial anticipating that upwards of 40 million would die. There is plenty of historical precedent to believe the maginitude of the WHO and Imperial’s epidemiological predictions; while COVID-19 is generally seen as not as fatal as the last global pandemic, the Spanish Flu, which resulted in 10-50 million deaths worldwide, many smaller pandemics of the 20th century including the 1957 A(H2N2) flu and the 1968 A(H3N2) flu resulted in millions of deaths each.

This person’s tweet greatly contradicts what most epidemiologists and models claim may be the potential danger of COVID-19, and has the potential to undermine public compliance with critical public health efforts. The ultimate cost of misinformation in this crisis could unfortunately be human lives.

As we think more deeply about online harms of misinformation in the future, might we have to look beyond the surface to ways that arguments or information might inspire audiences to arrive at incorrect conclusions?